Blog

Los tiempos verbales son misteriosos y a veces funcionan de manera desconcertante (que causa sorpresa, de manera extraña). Por ejemplo, uno podría pensar que el futuro simple, como su nombre indica, siempre se refiere a acciones que ocurrirán en el futuro. Sin embargo, no es así. Hoy vamos a hablar sobre un uso inesperado del futuro simple (yo hablaré, tú hablarás, etc.), y sobre otro uso, este probablemente menos sorprendente, del presente (yo hablo, tú hablas, etc.).

Un muerto en la cocina

Todos sabemos que el futuro simple expresa futuro. Algunos ejemplos: mañana iré a Nueva York / Esta noche saldremos a bailar / El año que viene compraremos una casa. Como hemos dicho, no siempre es así y vamos a explicarlo con la ayuda de un estudiante. Hace algunos años el gran Assad, un estudiante que ahora es prácticamente bilingüe, me mandó un correo para describirme la escena de una película española que yo no había visto todavía, “Volver”, de Pedro Almodóvar. En la escena, un ama de casa (una mujer cuyo trabajo es ocuparse de las tareas de su casa) interpretada por Penélope Cruz está en la cocina de su casa junto con su hija. En el suelo está el cadáver (el cuerpo sin vida, un muerto) de su marido que, por cierto, no ha fallecido (no ha muerto) de muerte natural. En ese instante alguien llama a la puerta. La madre y la hija se miran aterradas y el personaje de Penélope Cruz le susurra (hablar en voz muy baja) a la hija: “¿quién será?”.

¿Quién será?

“Será” es el futuro del verbo ser pero, sin embargo, en esta situación no expresa futuro. Alguien ha llamado a la puerta y esta persona está en este momento, en el presente, al otro lado, esperando que Penélope abra la puerta. En esta situación lo que expresa “será” es una conjetura o probabilidad en el presente. Es decir, “¿quién puede ser la persona que acaba de llamar?”, “¿quién crees que puede ser?”, “¿quién será?”. Assad estaba muy contento porque descubrió en una película lo que habíamos visto es clase. No recuerdo la respuesta de la hija de Penélope Cruz en la escena pero probablemente sería algo así: “no sé, será el vecino”; “será el vecino” es lo mismo que “tal vez es/sea el vecino”, “puede que sea el vecino”, “es probable que sea el vecino”. Es decir, otra vez el futuro, “será”, para expresar una probabilidad sobre el momento presente.

A partir de entonces, Assad empezó a reconocer este uso del futuro en sus charlas (conversaciones) con amigos latino porque la verdad es que es muy común. Más ejemplos: si alguien te pregunta “¿cuántos años tiene Bob Dylan?”; tú no estás muy seguro pero si crees que puede tener 74 o 75, entonces una posible respuesta sería: “no sé, tendrá unos 75”. Un tercer ejemplo: alguien quiere saber dónde está tu hermano y tú no lo sabes con seguridad pero sí sabes que son las diez de la mañana y que tu hermano va a la universidad. La respuesta podría ser: “estará en clase”. Es decir, es posible o probable que ahora mismo, un lunes a las diez de la mañana tu hermano esté en clase. La manera más coloquial de expresar esto es “estará en clase”. En el podcast “Riding my bike in Maryland and DC” encontrarán más información sobre este uso del futuro como conjetura o probabilidad en el presente.

Presente que expresa futuro

Acabamos de ver que el futuro puede muy bien expresar presente. Parece muy justo entonces que, en reciprocidad, el presente pueda expresar futuro. En realidad, el presente es un tiempo verbal bastante misterioso porque puede usarse para referirse al pasado, al futuro y al propio presente. Veremos todo esto otro día para centrarnos hoy en el presente que expresa futuro. Un ejemplo: el jueves que viene tomarás un par (dos) de semanas de vacaciones. Por supuesto puedes decirlo usando el futuro y también ir + infinitivo: el jueves me iré de vacaciones un par de semanas / el jueves me voy a ir de vacaciones un par de semanas. Sin embargo, yo diría que la manera más coloquial de expresarlo es usando el presente: el jueves me voy de vacaciones un par de semanas.

Es un uso muy corriente (común, habitual) del presente. Lo oirán constantemente en conversaciones con hispanohablantes. Es importante recordar que, en estos casos, el presente suele ir acompañado de una palabra que nos recuerda que la acción se refiere al futuro. Estas palabras que ayudan al presente a expresar futuro son numerosas: la semana que viene, esta noche, mañana, el próximo año, después, más tarde, etc. Más ejemplos: estás hablando por teléfono con tu pareja pero tienes que colgar (terminar, poner fin a la conversación telefónica) y te despides así: “bueno, hablamos esta noche”. Más ejemplos: el año que viene me compro el coche / Este fin de semana hago una paella.

Aquí les dejo ahora unos cuantos ejercicios sobre los dos usos del futuro que hemos visto. Recuerden que en nuestras guías didácticas encontrarán explicaciones gramaticales y muchos más ejercicios.

Literally translated a “falso amigo” in Spanish means a “false friend”—when referring to grammar, it may not make much sense in English, but in Spanish it is used to refer to words that are alike in form in both languages but vary in meaning. We, Spanish teachers, should take advantage of “falsos amigos” because they give us a chance to identify a problem and help students improve.

A “falso amigo” or “falso cognado”, or in English a “false cognate”, is a word that “sounds” more or less the same in both English and Spanish, but whose meanings and usages are often very different. In this article we will take a look at three of the most “infamous” false cognates. Let´s start with the most commonly referenced example of “falso amigo”, the mistaken use of the Spanish phrase: “estar embarazada” for the English “to be embarrassed”. Let´s illustrate this with an anecdote.

An anecdote

One day several years ago, I was on my way to meet Pam and Todd, at the time a couple recently married who were learning Spanish with me, to have our weekly class. I received an urgent phone call from home–it was my wife. She was calling to ask me to come home quickly to take her to the emergency room. She was a few weeks pregnant; “embarazada” as we say in Spanish, and she was not feeling well. I called Pam to tell her—in Spanish—what was going on; she understood perfectly that the class was to be rescheduled since I had to take Valeria, my wife, to the hospital, but was confused as to why Valeria was “embarrassed” about the situation, because as she noted, “Everybody has the right to get sick!” The next class with Pam and Todd was fun, but also a milestone. I explained that “estar embarazada” does not mean “to be embarrassed”, but to be pregnant. We laughed a lot about the misunderstanding and began to practice every week with a “falso amigo”. Also, I told them that if you are embarrassed, in Spanish you should say “estoy avergonzado” (personally I would say “¡qué vergüenza!” in most cases).

To realize

Though it is a notable “falso amigo” to use “estar embarazada” for the English “to be embarrassed”, in the hundreds and hundreds of hours I have invested in teaching, I have only heard it misused a handful of times. Let´s take a look at another more commonly used “falso amigo”, and let’s try it in Spanish:

Pedí un café en Starbucks pero cuando iba a pagar me realicé que no tenía dinero.

Los niños no se realizan que el dinero no es gratis.

In English the verb “to realize” has two main meanings: 1. “To become aware of” or “appreciate” and 2. “To accomplish” or “to bring to fruition”. Conversely, in Spanish the verb “realizar” has as well the second meaning of the English verb -“to carry out or execute” as in a task- but not the first one. Therefore, it is not correct to use “realizar” for the first meaning of “to realize”, as it is a “falso amigo”. To properly express the first meaning of “to realize” –“to become aware of” – in Spanish we must use “darse cuenta (de que)”. For example:

Pedí un café en Starbucks pero cuando iba a pagar me di cuenta de que no tenía dinero.

Los niños no se dan cuenta de que el dinero no es gratis.

Success

Here we have another classic. We have talked about success in the recent Podcast En Spanish Intermediate 002 – In latino homes, bilingual children? , but let´s put it in writing.

La reunión fue muy bien. Fue un “succeso” de todo el departamento.

Lots of times Spanish teachers have heard things like this in class. Students think about “success” and they figure out that a similar word with the same meaning must exist in Spanish. But “succeso”, does not exist in Spanish, and “suceso” would translate for event, incident. The word for “success” is “éxito”. Some examples of use:

- España ganó la Copa del Mundo de Sudáfrica en 2014. En mi opinión, Xavi Hernández fue el futbolista más importante de este gran éxito.

- Steve Jobs tuvo éxito con casi todos sus productos.

On the other hand, the English word “exit” has its own “falso amigo”. As you can guess, it does not translate for “éxito, exit”, etc. Let´s put it wrongly, as we heard often in the classroom:

Cuando voy al cine a ver una película siempre miro dónde está el éxito más cercano.

La palabra correcta es “salida”. Ejemplo de uso:

Para ir a Manor Rd. desde la (carretera de circunvalación) 495 tienes que tomar la salida 33. Entrarás en Connecticut Avenue. Manor Rd. es la tercera o la cuarta calle a la izquierda.

Summarizing

The English and Spanish languages have lots of words which share common roots, a common etymology -mostly from Latin. Through the centuries these words have frequently -and little by little- followed different semantic paths. That´s the way “falsos amigos” have originated. They are here to torture us a little bit and, sometimes, to make us laugh.

(Note: This article has been rewritten from a former version published several years ago).

Los tacos de este episodio no se comen. Estos tacos son groserías, palabrotas, obscenidades, etc. Valeria y Santiago hablan de los que más se usan en el lenguaje coloquial en México y en España. Este episodio puede herir la sensibilidad de algún oyente. Warning: This podcast contains adult language. Listener discretion is advised.

I have always thought that the old Italian adage “traduttore, traditore” (literally “translator, traitor”) has a little truth to it even when you count on the best translator in the world. There is something you lose irremediably when reading a translation. I am not talking here about a tricky translation, like the classic example of how in translating to Spanish the Oscar Wilde “The Importance of Being Earnest”, the English title plays with the double sense created by the same sound of “earnest” and “Ernest”. This double meaning does not exist in Spanish. The Spanish translation generally accepted is “La importancia de llamarse Ernesto”, which loses the innocent and delicious joke that is to be in English. But this is an extreme and a difficult case. Instead I am referring here to regular translations, to something more subtle, you can call them maybe the tone, some nuances, “the music” of the language. Not so long ago I enjoyed a lot reading “El retrato de Dorian Gray” in Spanish–for continuing with Wilde- but now being able to appreciate in English “The portrait of Dorian Gray, the actual thing, it is a different and obviously much richer experience.

A little experiment

I have carried out the experiment of reading some pages in English of “don Quixote of La Mancha”. Honestly you can say that these translations are excellent -and they are as excellent as they can be- but something is inevitably lost on the way. “Toto, we are not in La Mancha anymore”. No doubt I can understand why great men like Freud or Dostoyevsky learned Spanish just to read “don Quijote”.

Translating to Spanglish at home

Now let´s jump a little from these great professionals –the translators- to my home, where my little daughters speak only in Spanish but sometimes they translate, and translate literally from English, which ends up literally tearing the language of Cervantes apart.

Mis manos

“Papá, me voy a lavar mis manos” (“I am going to wash my hands”) says the little one after arriving home from her daycare. Here is a perfect example of Spanglish! “Lavarse” is a reflexive verb, so you should not use the possessive adjective “my” (“mis”) because everyone already knows you are referring to your own hands because of the reflexive pronoun “me”. How can one avoid this common mistake? By repetition, and by answers and questions . “Papá, me voy a lavar las manos” I say with special emphasis on “las”. Then she repeats the correct phrase. If both she and I are not too tired I keep asking: “hija, ¿vas a lavarte las manos?” – “Sí, papá, voy a lavarme las manos”. Sometimes it takes weeks to avoid this use of the possessive adjectives (mi, tu su, etc.) instead of the determined article (el, la los, las). But when it happens, when the girls are able to say it naturally in actual Spanish I know that my daughters will become truly bilingual (I know very, very, few truly bilingual people. I am afraid I will never become one of them, but I’ll keep trying!).

Mi bufanda

Another classic example in winter time, “¿tengo que ponerme mi bufanda?” (do I have to put my scarf on?). My wife and I use to correct her at the same time “¿tengo que ponerme la bufanda”. It´s kind of comical. These corrections in stereo from my wife and I have become a family joke, but that shows our commitment. In my view, it is the way to go. Please, teach your teacher to teach you in this way. Tell her/him “pregúntame si voy a lavarme los dientes” (“ask me if I am going to brush my teeth). He or she should ask you tons of times those types of questions with different verbs and situations until you master it.

Mi garganta

This little horror also happens often with verbs that take an indirect object like “doler” (to hurt), and the subject is a part of the body (me duele, te duele, le duele, etc.). My oldest, who is 8, told me the other day from the back seat of the car: “papá, me duele mi garganta” (my throat hurts). I forgot about proper Spanish and asked her the usual things good parents are supposed to ask on these circumstances, but I must confess, my initial impulse was tell her that she should have said “me duele la garganta”. Well, to adapt an English adage “once a teacher, always a teacher”. However, I thought, it could have been definitely worse with a completely literal translation “mi garganta duele”). Sometimes, Spanish speakers use the possessive adjective, but it is with a special, affectionate emphasis: “¿te duele tu pancita? (”Does your stomach hurt?).

Literal translation

There are countless examples where literal translation is grammatically wrong or, at least, it sounds a little weird to a Spanish speaker. We will work on them with a little help from my little translator daughters. They are a treasure for a Spanish teacher! I guess sooner or later, they will end up asking for copyright… and royalties for these posts.

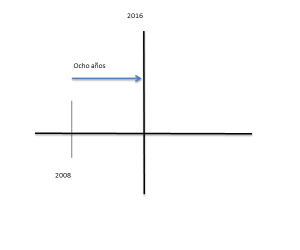

Estas dos estructuras se utilizan para expresar que la acción empezó en el pasado y continúa en el presente. Por ejemplo: “hace ocho años que vivo en Silver Spring” expresa lo mismo que “llevo ocho años viviendo en Silver Spring”. Yo diría que el uso de “llevar” es más coloquial que el de “hace” y se usa más en el lenguaje hablado. Por el contrario, es probable que “hace” se utilice más que “llevar” por escrito.

Empecemos con “hace”. El verbo hacer -yo hago, tú haces, él hace, etc.- también puede ser impersonal. Cuando funciona como verbo impersonal solamente tiene una forma, que es igual que la tercera personal del singular, “hace”. Recordemos que un verbo impersonal no tiene sujeto y tampoco tiene plural. Por ejemplo, un uso muy común de “hace” como verbo impersonal es para hablar del tiempo: hace buen tiempo, hace calor, hace frío, hace viento. La palabra “viento” en “hace viento” no es el sujeto, es un objeto directo. “Hace viento”, “lo hace”. Sin embargo, en “Juan hace los deberes”, “hace” no es un verbo impersonal puesto que tiene un sujeto, “Juan”.

Hace más verbo en presente

Otro uso de “hace” como verbo impersonal es el que nos ocupa en este artículo. El ejemplo mencionado, “hace ocho años que vivo en Silver Spring” sería gráficamente algo así considerando que estamos en el año 2016:

Esta estructura es muy flexible y nos permite jugar un poco. Vamos a ver ahora tres posibles construcciones que expresan básicamente lo mismo:

- Hace + tiempo (años, horas, etc.) + que + verbo en presente / Hace ocho años que vivo en Silver Spring.

- Verbo en presente + hace + tiempo (años, horas, etc.) / Vivo en Silver Spring hace ocho años.

- Verbo en presente + desde hace + tiempo (años, horas, etc.) / Vivo en Silver Spring desde hace ocho años.

Las tres construcciones indican que la acción empezó en el pasado (en 2008) y continúa en el presente (en septiembre de 2016).

Para preguntar la estructura más común es esta:

¿Cuánto + tiempo + hace + que + verbo en presente? / ¿Cuánto tiempo hace que vives en Silver Spring?

En las preguntas la palabra tiempo puede sustituirse por años, días, meses, horas, etc., y también puede desaparecer por completo porque estaría implícita. Las tres posibles preguntas:

- ¿Cuánto tiempo hace que vives en Silver Spring?

- ¿Cuántos años (meses, semanas, etc.) hace que vives en Silver Spring?

- ¿Cuánto hace que vives en Silver Spring? Aquí la palabra “tiempo” está implícita. Probablemente es la estructura más coloquial y utilizada.

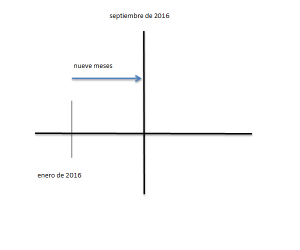

Llevar más gerundio

Esta construcción -llevar + tiempo (años, días, horas, etc.) + gerundio- expresa lo mismo que hace + presente. Es decir, la acción empezó en el pasado y continúa en el presente. El tiempo (semanas, meses, etc.) podemos colocarlo entre “llevar” y el gerundio o al final de la frase.

- Llevo nueve meses estudiando español. (“Llevar” en presente + tiempo + gerundio)

- Llevo estudiando español nueve meses. (“Llevar” en presente + gerundio + tiempo)

Gráficamente:

En las preguntas – al igual que en la construcción con “hace”- la palabra tiempo puede sustituirse por años, días, meses, horas, etc., y también puede ir implícita. Tres posibles preguntas:

- ¿Cuánto tiempo llevas

estudiando español? - ¿Cuántos meses (días, años, etc.) llevas estudiando español?

- ¿Cuánto llevas estudiando español?

Una breve recomendación. A veces en clase un estudiante dice algo así: “he estado viviendo en Silver Spring por ocho años”. Estas construcciones con tiempos progresivos son raras en español. Uno se percata (se da cuenta, adivina, comprende) inmediatamente que es una traducción literal del inglés y, la verdad, no funciona. Las dos maneras correctas y coloquiales de decir esto son las que hemos visto: hace ocho años que vivo en Silver Spring / Llevo ocho viviendo en Silver Spring. Prometo escribir algún día un artículo sobre estas formas progresivas o continuas en español, sobre cuándo son admisibles y cuándo no.

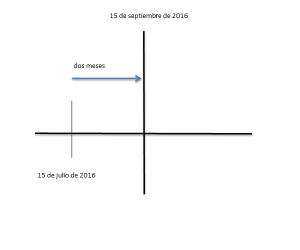

Otro ejemplo

Veamos ahora otro ejemplo pero les propongo jugar un poco. Les voy a dar el gráfico y la pregunta y ustedes tienen que tratar de dar todas las respuestas posibles con las estructuras que hemos visto, ¿vale? (¿de acuerdo?, ¿está bien?, ¿les parece bien? (“Vale” se usa en España).

La pregunta: ¿Cuánto hace que Juan vive en DC? / ¿Cuánto lleva Juan viviendo en DC?

Respuestas con hace + presente:

- Hace dos meses que Juan vive en DC.

- Juan vive en DC hace dos meses.

- Juan vive en DC desde hace dos meses.

Respuestas con llevar + gerundio:

- Juan lleva viviendo en DC dos meses.

- Juan lleva dos meses viviendo en DC.

Dos particularidades con llevar

Me gustaría terminar con un par de notas sobre “llevar”. La primera es que a veces puede prescindirse del gerundio y la oración expresa exactamente lo mismo. Esto se hace frecuentemente en las respuestas porque el gerundio está implícito. Por ejemplo:

-¿Cuánto llevas viviendo en DC? – Llevo solamente un par de meses.

En otros casos podemos prescindir del gerundio en la pregunta simplemente porque el contexto nos ayuda a entender esta pregunta. En estos casos suele haber una referencia al lugar; la idea de “lugar” (DC, aquí, etc.) suele estar presente. Por ejemplo, “Juan lleva dos meses en DC/¿Cuánto lleva Juan en DC?”. En efecto, el gerundio está implícito: “Juan lleva dos meses viviendo en DC/ ¿Cuánto lleva Juan viviendo en DC?”.

El segundo comentario. Esta construcción de llevar + gerundio tiene que expresar negación con la preposición “sin”. Por ejemplo, “hace dos meses que Juan no fuma” sería “Juan lleva dos meses sin fumar”; “Juan lleva dos meses no fumando” no es correcto. Es decir, en este caso el gerundio se transforma en infinitivo. Recuerden que siempre que hay una forma verbal después de preposición tiene que ser un infinitivo.

¿Listos para los deberes? (Deberes es España, tarea en América). Al final de este artículo encontrarán las respuestas y, por favor, recuerden que si están interesados en nuestros cuadernos de ejercicios los encontrarán aquí.

Ejercicios. Hacer con presente / llevar más gerundio

Several weeks ago I noticed that my youngest daughter, who is 4, began saying things like “papá, quiero a desayunar”, “papá, ¿quieres a jugar conmigo?”, etc. Usually I corrected her: “papá, quiero desayunar”, “papá, ¿quieres jugar conmigo? and the like. Sometimes my wife looked at me as if thinking, “You are not going to give her a grammar explanation, are you?” Well, no, – at least not yet- but I could not help thinking about where this “a” was coming from. Please, do not be fooled. I have been explaining for years to my students why this “¿quieres a comer?” is a wrong construction, but in this case the simple explanation it was just not enough for me. Why? Because she used to say it well.

The answer came one morning in my daugther´s day care. I was taking her jacket out when I heard in a good Spanish accent “hola, ¿quieres a desayunar? I turned around and saw the nice Miss P. looking at us, smiling, very proud about her Spanish. I doubted for a second, but I decided to go ahead. If I had been she, I would have appreciated someone correcting me.

I explained to her that in Spanish the infinite has just one word –comer, hablar-, and she was translating literally the two words from the English infinitive, figuring out wrongly that “to” would translate as “a”. Consequently, I told her “to speak” translates “hablar”; not “a hablar”; “to have breakfast” translates to desayunar (tener desayuno is a matter for another article). Then, the right question would be “hola, ¿quieres desayunar?”. Miss P. said “I understand. Thank you” and kept working.

As for my daughter, I thought that her many hours of daily English plus a little help from Miss P. had resulted in this “quiero a desayunar”. And as for Miss P., to be honest I felt uneasy all day. I began thinking that I might have sounded like a rude foreigner who is not familiar with good American manners, or maybe I looked like an upset father who did not want his daughter´s teacher to practice Spanish with the child. Besides, her bosses might have said something to her.

Next morning, my little one and I entered the daycare. The usually good humored Miss P. was working, as usual, but she did not even look at us. I told her aloud to be heard by all the teachers, “Miss P., would you like to practice your Spanish?” She looked at us, gave us a big smile and said aloud in a perfect Spanish “Sí. Hola, ¿quieres desayunar?” Her colleagues –and her boss- laughed and began clapping. My daughter and I too.

¿Español o castellano?

Sometimes prospective students tell us that they don’t want to learn Spanish (español) but “castellano” (Castilian), or “the Castilian dialect”. Sometimes, other people ask to learn the Latin American Spanish; not the “castellano” dialect. Let us clarify a few things.

Español = castellano

There is only one language, and you can call it “español” (Spanish) or “castellano” (Castilian). For sure, there are different accents in the same way that a Texan and a Bostonian share the same language –not trying to joke here- but have different accents. We will address what to call the language of Cervantes and the main differences between the Spanish (or Castilian) from Spain and the Spanish (or Castilian) from Latin America –if you consider the Spanish from Latin America as a whole, which is a matter for another posting.

About the name of the language, which should we choose, “español” or “castellano”? Many years ago, when I worked in Madrid for an Iberoamerican Educational TV station, I asked Víctor García de la Concha, then director of the Real Academia Española, and currently director of the Instituto Cervantes, this question. He answered me “muy fácil” (very easy), and told me, more or less, that when in Spain –where I am originally from- you should say “castellano” because there are other languages there like Catalan, Basque or Galician, but when you are not in Spain you should say “español” because it is the way that the language is recognized everywhere. This is especially true in the USA, although the name “castellano” is prefered to “español” in some countries like Argentina. So, generally speaking we should say “español” world wide except in Spain, where we should say “castellano”. Because I am very obedient I have done so since I spoke with the great man. Besides, I followed his directions even in its spirit. I live in the Washington DC area and here and there I talk to other Spaniards who, besides Spanish, our common language, speak Catalan, Basque or Galician. In these circumstances, I always refer to our common language as “castellano”.

The pronunciation of the letters c and z en Latin America and Spain

That said, there are two main differences between Latin American Spanish and the Spanish from Spain. The first difference has to do with pronunciation of the letters “c” (just syllables “ce” and “ci”), and the letter “z” which are both phonetic in Spain, (except in Andalucia and the Canary Islands). In Spain they are pronounced as in “ think”, ([th]ink). I have this phonetic pronunciation. Take the pronunciation of “ce” on “cena” (dinner), and “ci” on “cita” (appointment)”. In Latin America and the south of Spain people pronounce them [s]; “cita” would be [s]ita, and ”cena” would be [s]ena. Take now “cerveza” (beer). “Cerveza” in Latin America is [s]erve[s]a”. My wife, who is half Costa Rican, half Mexican has this “Latin American” pronunciation.

I would like to go a little deeper about into letter “c”. Like I said, in Spain it has this pronunciation ([th]ink) just with the vowel “e”, as is “cerca” (near) and the vowel “i”, as in “cine”. In Latin America it would be [s]erca and [s]ine. How about with the other vowels? With the other vowels the letter “c” is pronounced with the sound “[k]” as is ([k]arate) in the entire Hispanic world. So, the “c” with the “a” is pronounced “ca” like in “casa”, “Canadá”; the “c” with the “o” is “co”, as is “cosa” (thing), “comer” (to eat); and the “c” with the “u” is pronounced “cu]”, as is “cuando”, “cual”.

Vosotros y ustedes

The second difference is the second person plural of the subject pronouns. In Latin America there is only one form for both formal and informal situations which is “ustedes”. When they ask “¿ustedes son americanos?”, you can´t be sure if you are being addressed formaly or informally. In Spain we have the same “ustedes” for the polite way that we would use in a professional meeting, for instance. But we also have the “vosotros” for daily use, even with people you have just met. We would say “¿(vosotros) sois americanos? So, which is the way to go, the American way, or the Spanish way? Which is better from the perspective of a student of Spanish as a Second Language? At the risk of being considered unpatriotic I would say that the “vosotros” form will never be used massively out of Spain. Why? Because nobody in Latin America or in the USA uses the Spaniard “vosotros”. I know the Real Academia Española would urge all Spanish teachers around the world to teach the “vosotros” and the corresponding verb endings

and pronouns (e.g. vais, coméis, os llamáis). Believe me, my fellow Spaniards, nobody wants to learn one more pronoun if that could be avoided. I have been teaching Spanish in the DC area for almost 10 years now. Who is interested in the “vosotros” pronoun and its conjugations? Spouses, boyfriends and girlfriends of Spaniards, people who are going to live there, and academics, scholars and the like. I know several of these amazing crazy people who have fallen in love with “vosotros”. I love them, but things are the way they are.

But what about the pronunciation? In my view it is not very important. In the end, the only thing that´s really relevant when trying to learn a language is the quality of your tutor, the way he or she teaches you. But if I were a student with the option of choosing between two big caliber tutors and one of them used phonetic pronunciation, I would chose this one. Just for one reason: You would have fewer spelling mistakes when writing. For example, if you pronounce “cita” the Latin American way, it is easy to write “sita” because you will tend to write the same way you pronounce “[s]ita”. With phonetic pronunciation you would avoid many spelling mistakes.

Vive la différence!

So, are there just 2 main differences between castellano from Spain and castellano from Latin America? Just the pronunciation of the letters “c” and “z” and “vosotros”? Well, on other posts we will talk about countless words and idioms –not to mention accents- that change not just from Spain to Latin America but from one country to another e.g. “piscina” (swimming pool) in Spain is “alberca” in Mexico; “resaca” (hang over) in Perú is “cruda” in Mexico; “los deberes” (homework) in Spain is “la tarea” in Latin America; boyfriend or girlfriend are “novio/a” throughout the whole Hispanic world, but all Chileans say instead “pololo/a”.

Just one language

To be honest, I have been a little arbitrary in this article because how do I dare to put in the same box, let’s say, the Spanish from Chile and the Spanish from Guatemala? Are they identical? Nope. And to begin with, how do I dare to consider the Spanish from Spain for one side and the Spanish from Latin

America for the other side? Well, just doing so for the sake of clarity. Should Mr. García de la Concha read this posting someday I hope he is not too severe with me…

Let´s finish with our point. You know British English and American English are not identical but there is only one English language. It is the same thing with the Portuguese from Portugal and the Portuguese from Brazil. And the same is true with Spanish, just one language, but you can call it “español” or “castellano”.

Cuando me preguntan cuál es el error más habitual (frecuente) entre los estudiantes principiantes siempre contesto que tengo que decir dos: “un otro” en vez de “otro” (o “una otra” en vez de “otra”) y una/la problema, una/la tema, una/la sistema en vez de un/el problema, un/el tema o un/el sistema, etc. Además de ser errores frecuentes son errores persistentes, no es fácil dejar de (poner fin a algo, “el año pasado dejé de fumar”) cometerlos (hacerlos). Hoy vamos a referirnos a estas palabras que terminan en /ma y son masculinas.

Para abordar (tratar, introducir) este asunto (tema), hay que recordar que las palabras que terminan en “o” son masculinas (el teléfono, el libro) aunque hay algunas excepciones como “la mano” o “la líbido” (“la moto” es una abreviatura de “motocicleta” y “la foto” de fotografía). Los maestros solemos (“soler” es hacer algo regularmente, con cierta frecuencia) decir a los estudiantes muy principiantes que las palabras que terminan en “a” son femeninas (la casa). Esta generalización resulta muy útil para explicar la concordancia de género entre sustantivos, artículos y adjetivos (La Casa Blanca) pero, en realidad, no hay una regla que diga (“diga” es subjuntivo, “no existencia”, no hay una regla que…) que las palabras que terminan en “a” son femeninas. ¿Por qué? Porque hay demasiadas excepciones (el planeta, el día, el gorila, el mapa, el yoga, etc.). Además, claro, hay que incluir muchas palabras que terminan en /ma.

Muchas palabras que terminan en /ma son masculinas: el diploma, el dogma, el enigma, el lema, el poema, el programa, el teorema, el trauma, etc. En muchos casos, estas palabras proceden (vienen) del idioma griego (el idioma que se habla en Grecia). Eran neutras en griego y en español tomaron el género masculino. Muchas de estas palabras tienen que ver (tienen relación con) las artes, con las ciencias, con la filosofía. El problema es que también hay muchas palabras que terminan en /ma y son femeninas: la alarma, la broma, la cama, la calma, la paloma, la rama, la firma, etc.

¿Cómo podemos saber si una palabra que termina en /ma es masculina o femenina? Bueno, yo no recomendaría memorizarlas. Es suficiente con familiarizarse (conocer un poco) con las más importantes, con las que se usan más. Además, si tienen dudas pregúntense: “¿esta palabra tiene que ver con el mundo de las ideas, con las artes? Si la respuesta es sí probablemente la palabra es masculina. ¿Esto les garantiza (asegura) que nunca se van a equivocar (confundirse, cometer un error)? Por supuesto que no pero, en fin, si al principio se equivocan no se preocupen demasiado, no es un “drama”.

Literally translated a “falso amigo” in Spanish means a “false friend”—when referring to grammar, it may not make much sense in English, but in Spanish it is used to refer to words that are alike in form but vary in meaning. We, Spanish teachers, love “falsos amigos” because they give us a chance to identify a problem and help students improve.

Literally translated a “falso amigo” in Spanish means a “false friend”—when referring to grammar, it may not make much sense in English, but in Spanish it is used to refer to words that are alike in form but vary in meaning. We, Spanish teachers, love “falsos amigos” because they give us a chance to identify a problem and help students improve.

A “falso amigo”, or in English a “false cognate”, is a word that “sounds” more or less the same in both English and Spanish, but whose meanings and usages are often very different. The most commonly referenced example of this is the mistaken use of the Spanish phrase: “estar embarazada” for the English “to be embarrassed”.

I remember several years ago, as I was on my way to meet Pam and Todd, long-time students of mine, to have our weekly Spanish class, I received an urgent phone call from home–it was my wife. She was calling to ask me to come home quickly to take her to the emergency room. She was pregnant; “embarazada” as we say in Spanish. I called Pam to tell her—in Spanish—what was going on; she understood perfectly that the class was to be rescheduled since I had to take Valeria, my wife, to the hospital, but was confused as to why Valeria was “embarrassed” about the situation, because as she noted, “Everybody has the right to get sick!” The next class with Pam and Todd was fun but also a milestone. We laughed a lot about the misunderstanding and began to practice every week with a “falso amigo”.

Though it is a notable “falso amigo” to use “estar embarazada” for the English “to be embarrassed”, in the hundreds and hundreds of hours I have invested in teaching, I have only heard it misused a handful of times. Let´s take a look at another more commonly used “falso amigo”, and let’s try it in Spanish:

“Pedí un café en Starbucks pero cuando iba a pagar me realicé de que no tenía dinero.”

“Los niños no se realizan de que el dinero no es gratis.”

In English the verb “to realize” has two meanings: 1. “to become aware of” or “appreciate” and 2. “to accomplish” or “to bring to fruition”. Conversely, in Spanish the verb “realizar” has only one use—similar to the latter in English—meaning “to carry out or execute” as in a task. Therefore, it is not correct to use “realizar” for the first meaning of “to realize”, as it is a “falso amigo”. To properly express the meaning of “to realize” in Spanish, we must use “darse cuenta (de que)”. For example:

“Pedí un café en Starbucks pero cuando iba a pagar me di cuenta de que no tenía dinero.”

“Los niños no se dan cuenta de que el dinero no es gratis.”

“Juan buscaba su bolígrafo sin darse cuenta de que lo tenía en la mano”

Try it out!

Send us up to three of your own examples in Spanish using the expression “darse cuenta (de que)” and we will do our best to correct them and send our feedback to you in a few days. Email examples to: nadieesperfecto@spanishtutordc.com. We will post the best examples on our blog.

Check back here every Friday to find new articles. You will have a chance to apply your Spanish skills by sending us your own sample sentences each week.

When beginner students start their Spanish lessons, typically they are told that masculine nouns end in “o” (teléfono) and feminine nouns end in “a” (casa). Well, the caveat to this over-simplification is that it is used only in order to easily introduce students to the rules of agreement in gender with nouns, articles and adjectives (La Casa Blanca, el teléfono rojo).

When beginner students start their Spanish lessons, typically they are told that masculine nouns end in “o” (teléfono) and feminine nouns end in “a” (casa). Well, the caveat to this over-simplification is that it is used only in order to easily introduce students to the rules of agreement in gender with nouns, articles and adjectives (La Casa Blanca, el teléfono rojo).

In all honestly, several pages could be written about exceptions and comments to the “feminine, a”, “masculine, o” convention – for instance: la mano (the hand), el día (the day).

The top winners among the many common errors that arise as a result of this “rule” occur with words that end with “-ma” include: “La problema es seria…”, “las temas (subject, topic) del artículo…”; “es una sistema perfecta”; “esta programa de televisión…”. These words (el tema, el problema, etc.) are masculine in spite of ending in “-ma”. Many words ending in “-ma” are masculine. More examples: el poema, el teorema, el clima, el fantasma (ghost) among others. Why the inconsistency? Most of these come from neutral words of Greek origin that were adopted in Spanish as masculine nouns. Notably, many of these words have some relationship with the arts and philosophy.

With that said, not all “-ma” words are masculine. For example: la cama, (bed), la broma (joke), la firma (signature, firm), etc.

My advice is not to memorize every exception. Instead practice with the more common words ending in “-ma” such as: el problema, el sistema, el tema, el programa, el clima, el poema. Sometimes you may have a doubt between the masculine or feminine form with words of “-ma” endings. Well, yes, but don’t worry–it is not “un drama”.

Los viernes

Check back here every Friday to find new articles. Usually you will have a chance to apply your Spanish skills by sending us your own sample sentences each week.

In English it sounds perfectly natural to say: “I wake up at 8:00 am. I eat breakfast at home, and then I drive 30 minutes. I arrive in my office at 9:00am.” Literally translated in Spanish would be: “Yo me levanto a las ocho. Yo desayuno en casa y luego yo manejo treinta minutos. Yo llego al trabajo a las nueve.”

If you say it this way in Spanish, your friends may cringe and make fun of you and say something in reference to what a big ego you seem to have. You see, expressing yourself in this literal translation, it comes across more as if you are a self-centered person who thinks only of himself than of actually simply describing your morning routine. The reason is that we Spanish speakers very rarely use subject pronouns in front of verbs (yo, tú, él, ella, etc.). They are not necessary since the ending of the conjugated verb already indicates the person who is completing the action, (i.e.: hablo can only mean “yo”, hablas can only mean “tú”, etc.). A similar problem arises when you refer to others constantly by “ella, ella, ella”, or “nosotros, nosotros, nosotros”.

The correct way to express the above example would simply be: “me levanto a las ocho, desayuno en casa y luego manejo treinta minutos. Llego a mi oficina a las nueve.”. You could start with one “yo”, as in “yo me levanto”, but you would be wise to say it no more than that.

With that said, there are exceptions, of course. If you need to emphasize, sometimes the use of the subject pronoun is helpful: “yo no cocino mal; yo soy un buen chef.”. This also helps to distinguish parallel structures: “yo voy a Boston y tú a California”.